Descriptive statistics and internal consistency of psychometric scales

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test (FIRST), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and Shift Work Disorder Index (SWDI). Total scores were derived by summing Likert-scale responses according to each tool’s standard protocol. Table 1 summarizes the mean, standard deviation, and distribution percentiles for each psychometric instrument. The PSS had a mean score of 17.89 (SD = 6.78), indicating moderate perceived stress levels. FIRST showed a mean of 19.15 (SD = 5.81), reflecting moderate susceptibility to insomnia under stress. PANAS-PA yielded higher positive affect (M = 29.87, SD = 7.24) compared to PANAS-NA (M = 23.29, SD = 7.61), while SWDI showed a moderate presence of shift work-related symptoms (M = 7.01, SD = 4.70).

Internal consistency of psychometric instruments

Internal consistency of the psychometric tools was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (\(\alpha\)), with \(\alpha \ge 0.70\) considered acceptable. All instruments demonstrated acceptable to strong reliability, as shown in Table 2. PANAS-NA had the highest reliability (\(\alpha = 0.815\)), followed by FIRST (\(\alpha = 0.783\)).

Intercorrelations among psychometric measures

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine relationships among PSS, FIRST, PANAS-PA, PANAS-NA, and SWDI scores (Table 3). Perceived stress (PSS) showed moderate positive correlations with insomnia vulnerability (FIRST; \(r = 0.351\)), negative affect (PANAS-NA; \(r = 0.305\)), and positive affect (PANAS-PA; \(r = 0.314\)), suggesting that higher stress levels are linked with emotional and sleep-related difficulties.Insomnia (FIRST) was strongly associated with negative affect (\(r = 0.522\)) and modestly with shift work symptoms (SWDI; \(r = 0.289\)). SWDI was weakly correlated with PSS (\(r = 0.278\)) and PANAS-NA (\(r = 0.281\)). PANAS-PA and PANAS-NA were only weakly related (\(r = 0.211\)), supporting their conceptual independence.

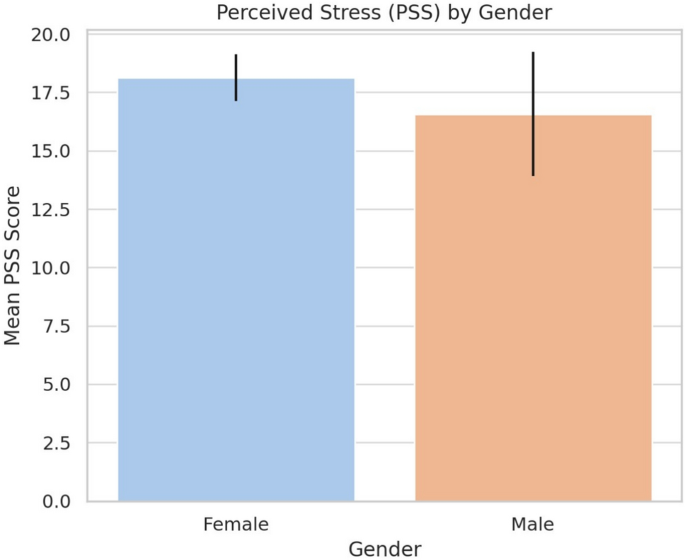

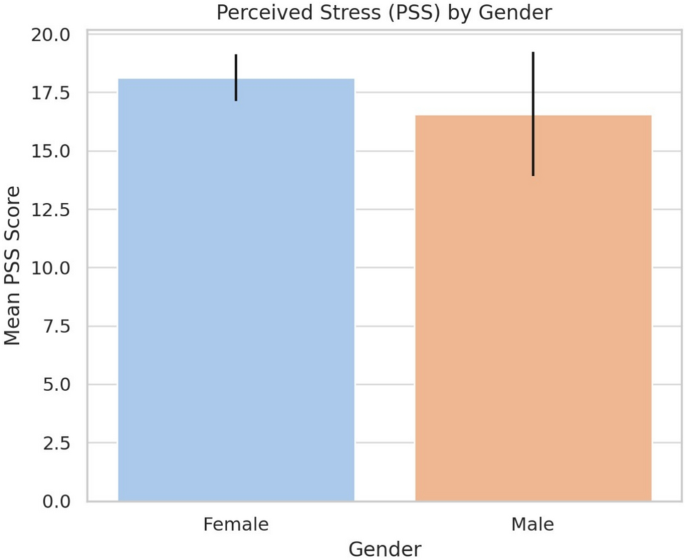

Gender differences in perceived stress

An independent samples t-test with Welch’s correction compared mean PSS scores by gender. As shown in Fig. 1, females reported slightly higher stress (\(M = 18.12\)) than males (\(M = 16.57\)), but the difference was not statistically significant (\(t = -1.07\), \(p = 0.292\)). Overlapping confidence intervals suggest no meaningful gender-based difference in perceived stress.

Perceived stress (PSS) by gender.

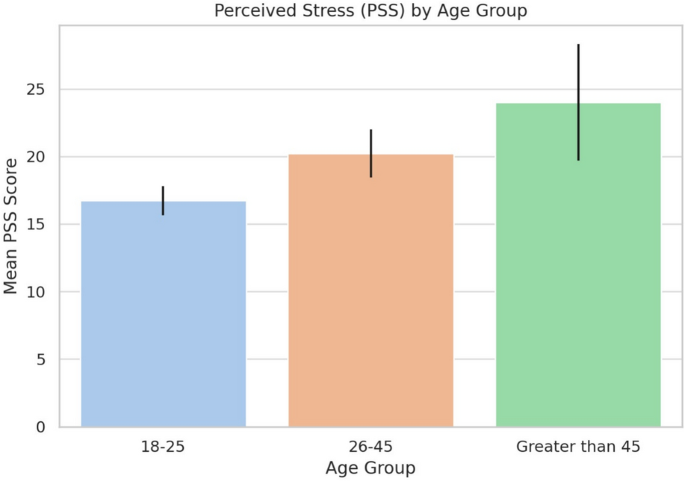

Age differences in perceived stress

A one-way ANOVA compared PSS scores across age groups (18–25, 26–45, >45). As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2, stress levels increased with age (\(p < 0.001\)), highest in the >45 group (\(M = 24.00\)), followed by 26–45 (\(M = 20.22\)), and 18–25 (\(M = 16.72\)). Due to the small size of the >45 group, results should be interpreted cautiously. Post hoc Tukey’s test (Table 5) showed significantly higher stress in the 26–45 group compared to 18–25 (\(p = 0.002\)); other comparisons were not significant.

Perceived stress stress (PSS) by age group.

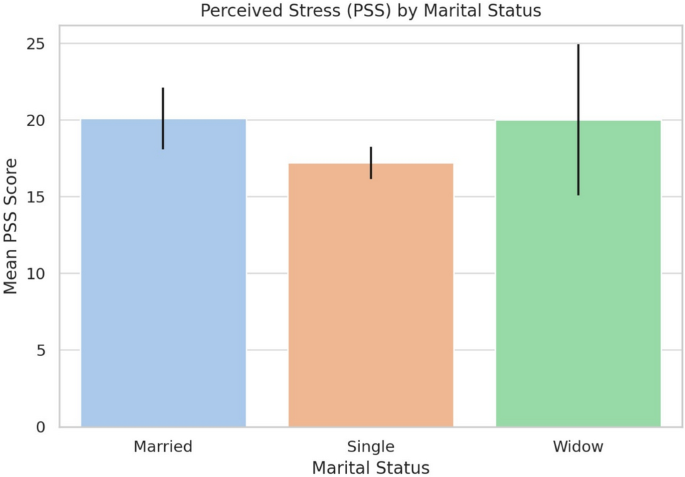

Marital status and stress

A one-way ANOVA assessed PSS differences across marital status groups. As shown in Table 6 and illustrated in Fig. 3, stress levels varied significantly (\(p = 0.035\)). Married participants reported higher stress (mean = 20.09) than singles (mean = 17.19). Widowed participants had a similar mean (mean = 20.00), but a wide confidence interval limits interpretation due to the small sample size.

Perceived stress stress (PSS) by marital status.

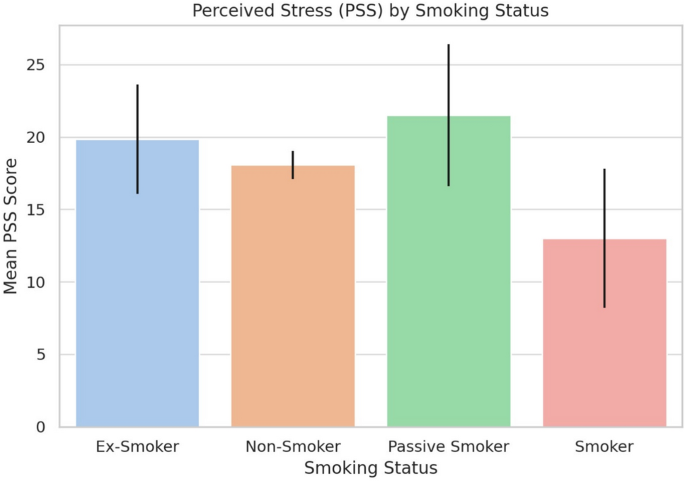

Smoking status and stress

A one-way ANOVA compared PSS scores across smoking groups: current, ex-, passive, and non-smokers. As shown in Table 7, and illustrated in Fig. 4 stress differed significantly by smoking status (\(p<\) 0.05). Passive smokers reported the highest stress (M = 21.50), followed by ex-smokers (M = 19.83), non-smokers (M = 18.07), and current smokers (M = 13.00). Wide confidence intervals in some groups reflect small sample sizes.

Perceived stress (PSS) by smoking status.

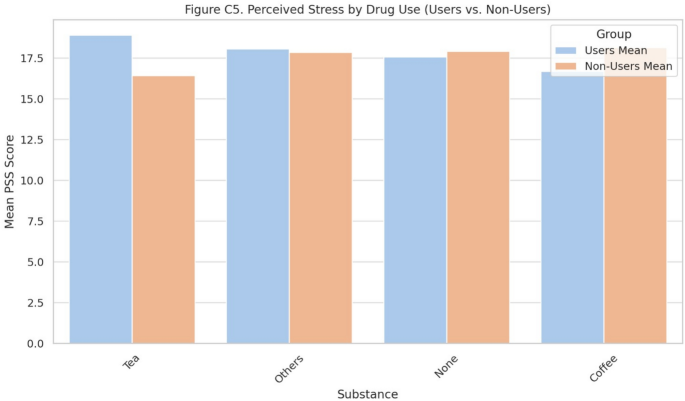

Substance use and perceived stress

Exploratory comparisons of PSS scores by substance use (tea, coffee, tobacco, marijuana, cigarettes, stimulants) are shown in Table 8, and illustrated in Fig. 5. Tea users (n = 117) reported slightly higher stress (M = 18.91) than non-users (M = 16.43). Tobacco and cigarette users showed lower stress, but subgroup sizes were very small. Marijuana and stimulant use were reported by only one participant each. Findings are preliminary due to limited sample sizes.

Perceived stress by drug use.

Body weight and stress

Correlations between body weight and PSS are shown in Table 9 and Fig. 6. Pearson’s r indicated a weak but significant positive association (\(r = 0.174\), \(p = 0.014\)), while Spearman’s \(\rho\) showed a similar, non-significant trend (\(\rho = 0.133\), \(p = 0.061\)). These results suggest a modest link between higher weight and stress.

Correlation between body weight and perceived stress.

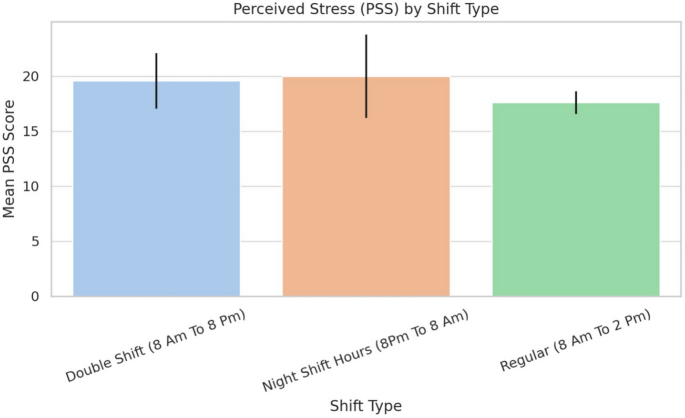

Shift type and stress

A one-way ANOVA assessed PSS differences across shift types: regular, double, and night. As shown in Table 10 and Fig. 7, night shift workers had the highest stress (M = 20.00), followed by double (M = 19.59) and regular shifts (M = 17.61). However, the differences were not statistically significant (\(p = 0.33\)), with wide confidence intervals indicating variability.

Perceived stress (PSS) by shift type.

Shift duration and perceived stress

A one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in PSS scores across daily shift durations (\(\le 6\), 6–12, \(\ge 12\) h; \(p = 0.24\)), although mean stress levels slightly increased with longer working hours (Fig. 8a). Similarly, another ANOVA assessed weekly working hours (<36, 36, 72, >72 h), with the 72-hour group showing the highest mean stress score (\(M = 19.37\); Table 11, Fig. 8b). However, this difference was not statistically significant (\(p = 0.619\)). Overall, neither daily nor weekly shift duration was significantly associated with perceived stress.

a Perceived stress (PSS) by shift hours per day, b Perceived stress (PSS) by weekly working hours.

Stress predicting negative affect

A linear regression assessed predictors of PANAS Negative Affect scores (Table 12). Perceived stress (PSS) significantly predicted higher negative affect (\(\beta\) = 0.325, \(p < 0.001\)). Mental health history also showed a significant association (\(\beta\) = 2.18, \(p = 0.036\)), while occupational injury was non-significant (\(\beta\) = 2.07, \(p = 0.129\)). The model intercept was 16.14 (\(p < 0.001\)). These results indicate that perceived stress strongly contributes to negative emotional states, beyond prior mental or injury history.

Multivariate predictors of perceived stress

A multiple linear regression was conducted using gender, age, marital status, smoking, drug use, and body weight as predictors of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores (Table 13; n = 200). Age emerged as the strongest predictor: participants aged 26–45 (\(\beta = 3.09\), \(p = 0.011\)) and over 45 (\(\beta = 7.95\), \(p = 0.041\)) reported significantly higher stress than those aged 18–25. Male gender showed a borderline-significant association with lower stress (\(\beta = -2.60\), \(p = 0.064\)). Body weight showed a weak, marginal association (\(\beta = 0.065\), \(p = 0.085\)). Smoking status (\(\beta = -4.94\), \(p = 0.152\)), marital status, and drug use were not statistically significant.Subsections 4.3 to 4.9 visualize the relationships between PSS scores and key demographic and lifestyle variables. These graphical trends support the regression model’s findings, particularly age as the dominant factor in stress variation. The results underscore the importance of age-specific, occupation-sensitive mental health interventions. The standardized beta coefficients indicate small-to-moderate effect sizes, suggesting that while statistically significant, demographic factors such as age exert a measurable but not overwhelming influence on stress levels in practical terms.

link